Making a killing: what can novels teach us about getting away with murder?

March 13, 2020From Agatha Christie to Gillian Flynn, readers love an untraceable method or a villain who wins. Author Peter Swanson says there are eight examples of the perfect murder

Is there such a thing as a perfect murder? In real life, the answer is probably yes, though how would we know about it? Perfection demands that the murder be unsolvable, maybe even unrecorded a victim disappearing off the face of the earth, a body never found, a killer never caught. In our world of forensic science and DNA evidence, the perfect murder must be as rare as a reclusive celebrity.

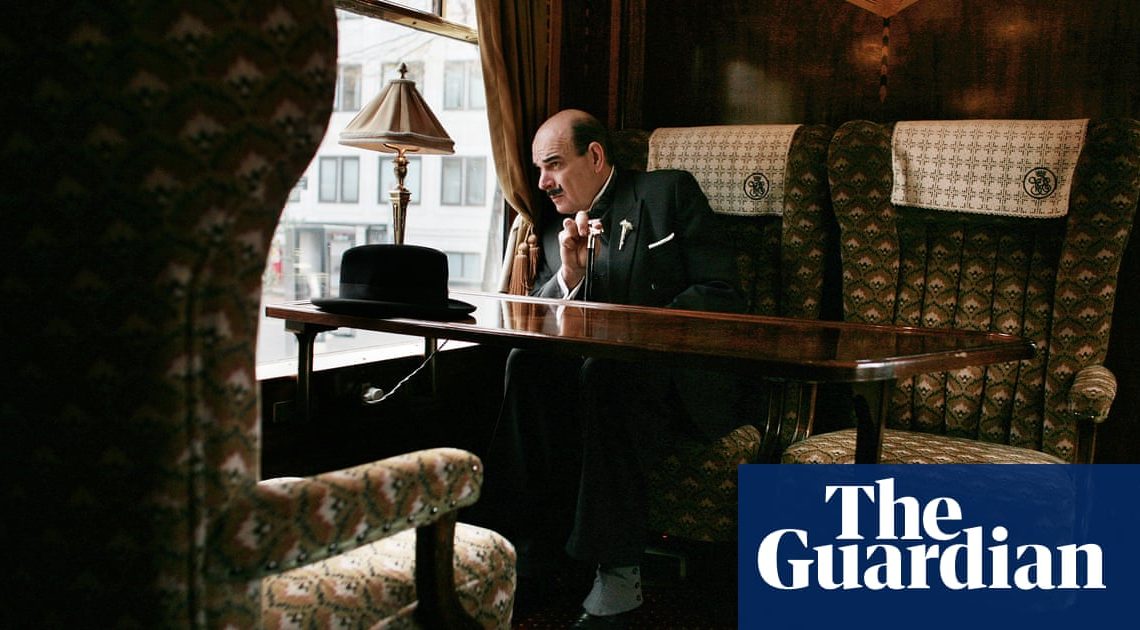

But we have fiction, and this is where we find an abundance of perfect murder attempts. I say attempts because the allure of most detective fiction hinges on the existence of an investigator a Holmes, a Poirot, a Lisbeth Salander who is smarter than the smartest of criminals. The perfect murder like a perfect sonnet or a perfect roast chicken is an ideal that can be approached but never entirely reached. Detectives, and storytelling tradition, get in the way.

When I set out to write a book in which a bookseller publishes a blog about his favourite fictional murders, only to find out that someone else is using the list as a blueprint for real crimes, I knew that part of the process of writing was going to be a whole lot of reading. So I set out to find a definitive list of perfect crimes and came up with a final tally of eight (or rather, my narrator Malcolm Kershaw did).

Those eight books include Strangers on a Train, Patricia Highsmiths venomous debut, which suggests the road to getting away with murder is for two killers to swap over their victims; Anthony Berkeley Coxs Malice Aforethought, practically a how-to guide for poisoning a spouse; and Donna Tartts chilly tale of undergraduate murder, The Secret History, in which a tight-knit group of classics majors dispatch one of their own.

What did I learn from making this list? That perfect murders, at least the artful kind we find in books, are all about concealment and misdirection. They have a lot in common with well-executed magic: its all about fooling the detectives (and the readers), making us look away from where the crime is happening. Agatha Christies The ABC Murders, another book on Malcolms list, is a textbook example: it appears as though a psychopath is bumping off victims according to the initials of their names, but the truth is something else altogether. Poirot, naturally, is not misled, and the world can be set to rights.

I could have included many more Christie novels on the list she is, after all, the undisputed master of the ingenious murder plot. And she loved misdirection. My favourite is Death on the Nile, in which the murderer(s) make sure that a witness sees something that doesnt really happen. Or think of The Mousetrap, her West End play that may yet run for ever (its currently clocking in at 68 years), in which a gun shows up in the hand of the last person the audience expects.

There are modern masters of misdirection, as well. Gillian Flynn created an iconic villain (or hero, depending on your point of view) with Amy Dunne, the star of Gone Girl. The brilliance of Amy was that shed had a lifetime of duplicity behind her. Not just as a child, starring in her parents series of Amazing Amy girl-empowerment books, but as a young woman in the dating arena, transforming herself into the mythical cool girl. So when it comes to framing her husband for her own murder, she is able to mislead an entire nation. Fake news as a spurned wifes revenge.

Unless you are a reader who studiously avoids anything on the darker end of the pop-culture spectrum, then you are, like me, spoilt for choice with delicious murder stories. The bestseller list has been filled for years now with girls who are victims, victimisers, witnesses, or some combination of all three. On TV streaming services, one could binge almost infinitely in the dark realms of a police procedural. Pick a location northern England, any Scandinavian country, the American city and the evil options seem endless.

Lately, there is a very definite trend for murderers who get away with it. Highsmith got there first, offering up Tom Ripley in five books filled with his unsolved crimes. Nowadays, just in the realm of TV, we have Dexter, the serial killer who hunts his own kind, and the cut-off-in-its-prime Hannibal, an artful, imaginative riff on the world of Thomas Harriss Hannibal Lecter. Then theres Ruth Wilsons sly performance as Alice Morgan on Luther, stealing the limelight from Idris Elba, and Jody Comers brilliant assassin in Killing Eve, adding a sense of humour to the killing game.

So much murder, so much of it committed with artful perfectionism so much so that crime fiction has been used as a blueprint for real-life murderers. In 1961, when Christie published The Pale Horse (an adaptation of which is on BBC iPlayer), thallium was a relatively unknown element. Its use as a fatal poison in this mystery story, and its description by the author as an effective tool for the removal of human beings, caused a brief uptick in the toxins presence in real-life crime. Graham Young, a serial poisoner, began experimenting with thallium right around the time of the publication of The Pale Horse, and it was alleged that hed been inspired by Christies novel. Im sure this was less than comforting news for Christie, although it might have been balanced out by the fact that the popularity of her book also saved at least one life when a nurse, who was a mystery fan, correctly diagnosed thallium poisoning in a young boy based on reading the book.

I was recently asked if Id keep a really foolproof idea for a murder to myself. I was unsure of the implication. Did the interviewer want to know if Id keep it out of the hands of a potential real-life criminal, or would I be keeping it to myself for possible practical application in the future (a particularly harsh book critic, maybe)? Regardless, my answer is a resounding no.

If I came up with a good juicy murder idea (and I like to think Ive managed a few), then I would most certainly include it in a book. Because the truth is that the vast majority of us, readers and writers alike, know the difference between fiction and reality. Its a truth that Edgar Allan Poe was well aware of when he wrote one of the first examples of a perfect murder in The Tell-Tale Heart. No matter how well you plan your murder, how perfect you make it, a human heart has stopped beating. If the police dont find you, something else guilt, karma, madness almost certainly will. Nothings perfect.

Peter Swansons novel Rules for Perfect Murders is published by Faber.

Read more: http://www.theguardian.com/us